Duels, Part II

sloppy thinking — duels of amity — bodies in motion, words in motion — screwball comedies — shakespearean kinship — casanova — wit, dexterity, and passion — stichomythia — plan 9 from outer space

Last week, in a sort of dazed stupor of despair brought on by prolonged reading about billionaires, I wrote that “I discovered that maybe fictional duels are as stupid as real ones.” Reader, they are not. Like anything else in art or life they are precisely as stupid as their creator makes them. There is a de Maupassant short story in which a man is challenged to a duel, spends a terrified sleepless night wondering if when the moment comes he’ll prove too much of a coward to hold his pistol steady, and chooses to prove his courage by blowing out his own brains. This is a stupid duel — the sort I feared, in my crisis of last week, might condemn all fictional duels. It’s a bleak ironical jab of nihilism. I have no patience for it and do not love it. But it is not representative of all duels in fiction any more than Lolita is representative of all love stories or Plan 9 From Outer Space of all science fiction movies.

My error was a lack of specificity. I spoke of “fictional duels” as though that means something, but it does not. “Duels” is not a genre of fiction. Duels may exist within stories that are romance or realism, tragedy or farce, and depending on where, when, and how they are deployed they will convey different things. Context and intention matters.

Where does that leave us? I both do and do not love duels. The institution is stupid, there is nothing wonderful in the institution. But there is plenty of love and wonder to be found in individual duels. (This piece is written for me — it’s me cleaning up a thoughtmess of my own making. I’ll keep it brief and next week we’ll return to our usual programming.)

Here’s what I’ve come up with in my noodling on duels.

We may broadly distinguish between three types: duels of enmity, duels of amity, and duels of ego. A duel of enmity is fought because two people dislike each other. A duel of amity is fought because two people either love each other and don’t yet realize it, or love each other but are having a tiff, or love someone else and are fighting on their behalf. A duel of ego is fought on principle, not for any rational reason (fighting because you say Tasso, who you have not read, is a better poet than Ariosto, who you also have not read, is a duel of ego).

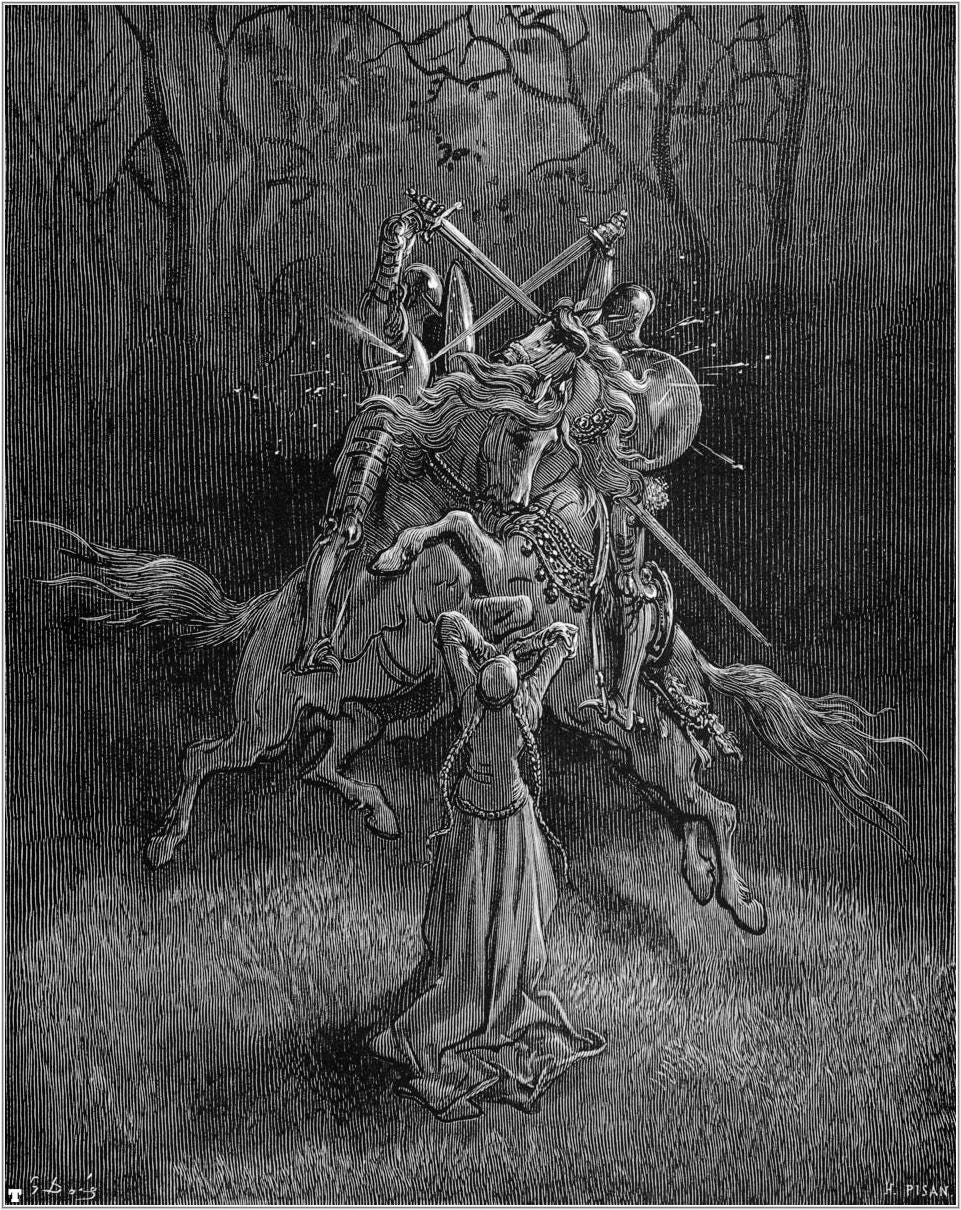

We may dispense with duels of ego and enmity — those are the Musk/Zukerberg thing. The duels I love are duels of amity. They show, counterintuitively, compatibility between the opponents. We see in their dance — because a good fencing match is a dance — that both physically and mentally they are well-matched. We see that they would be good friends or good lovers.

Bodies in motion thrill me. Watching Errol Flynn and Basil Rathbone shadowdance their way through the great hall in their not-duel, or Michelle Yeoh and Chow Yun-fat and Zhang Ziyi and Chang Chen float through bamboo forests and gallop through deserts in their probably-are-duels, is beautiful in the same way it’s beautiful to see Misty Copeland soar across the stage of the Lincoln Centre or Jamie Bell tap his way down the ballet-averse streets of Durham. It’s all poetry in motion.

It has a verbal equivalent (language in motion is no less thrilling than bodies). There’s a Greek word, stichomythia, that means a quick back-and-forth volley of dialogue in a play. (In its strictest definition it’s limited to exchanges in verse, but usage has evolved.) It’s the opposite of speechifying. Character A says a single line to which character B responds with a single line to which character A responds with a single line, etc. It’s rapid-fire patter, used to convey heightened feeling and moments of passion — romantic, intellectual, or violent. Arguments and love scenes are often built of stichomythia. Screwball comedies and film noirs are filled with stichomythia. His Girl Friday is made of virtually nothing but. Sitcoms use it. Aaron Sorkin loves it.

Even when the dramatic stakes are high stichomythia has a swagger and panache. It’s sexy. It’s smart. It’s sexy because it’s smart. Dumb characters don’t talk in stichomythia — it demands a quick wit and a ready tongue. There’s nothing slow or measured about it, there’s no room for breath or thought. The words are the thought. In its entry on stichomythia the Encyclopedia Britannica repeatedly uses fencing terminology: “repartee” (from a French term that meant “an answering blow or thrust”), “cut-and-thrust,” “cut-and-parry,” “riposte.”

Stichomythia is a fencing match in words.

1938 was a good year for fencing in movies. It gave us not only The Adventures of Robin Hood, but also Holiday and Bringing Up Baby, both starring Cary Grant and Katharine Hepburn. Grant and Hepburn are fencers every bit as as adept as Flynn and Rathbone, but their weapons of choice are words not swords. A few years before Edward R. Murrow would say that Winston Churchill mobilized the English language and sent it into battle, Grant and Hepburn met in a field at dawn and with great verve and dash went at one another with flashing sallies of wit until one realized the only way to stop the other’s mouth was with a kiss.

The twin fountainheads of the screwball comedy are Much Ado About Nothing and A Midsummer Night’s Dream (both of which Bringing Up Baby nods to explicitly); the fountainhead of the swashbuckler is Romeo and Juliet. They are Shakespearean siblings.

In 2005 the great Swedish director Lasse Hallström recognized this kinship and combined the screwball and the swashbuckler to make the criminally underseen Casanova. In it, Heath Ledger and Sienna Miller fight one of the most delightful of all cinematic duels — it is both duel-as-farce and duel-as-love-scene, which are the two best uses of a duel.

The facts are these: Ledger’s Casanova, a notorious but good-hearted rake, has been ordered by the Doge of Venice to marry Victoria Donato (Natalie Dormer’s first screen role), “the last Venetian virgin,” that by their union he may Become Respectable. But the boy next door (played by baby Charlie Cox; seriously, everybody needs to see this movie) is in love with Victoria, sees Casanova leaving her house, and without knowing who he is dashes out to challenge him to a duel. But he’s bad at it and somehow manages instead to engage a duel with Casanova’s servant, Lupo Salvato (Omid Djalili). But Casanova and Lupo are good buddies and Lupo cannot fence, so Casanova, masked, fights in his place. The blushing boy next door also cannot fence, so his big sister Francesca (Miller), who not only can fence but also secretly publishes — under a male pseudonym — feminist tracts condemning Casanova (whom she has not met) insists on fighting in his place.

So the duel ends up being fought not by its ostensible principals but in fact by their seconds, and those seconds happen to represent two seemingly-opposed positions (he, male hedonism; her, feminist agency), and they happen also to be attracted to one another (which they discover both through their sweaty vigorous thrusting and subsequently through their postbellum philosophical wordplay), and they meet under names by which neither may recognize the other.

This is the sort of duel I love. At no point does the viewer wonder if anyone’s life is at risk. What’s more, the participants in the duel know duels are stupid, and fight only to protect those they love. We get to have our cake and eat it, too: even as we laugh at the farce and smile at the wit, the athleticism and eroticism of their dance is on full display. Swashes are buckled and balls are…danced.

Duels in life were stupid and often tragic affairs. Duels in fiction needn’t be. At their best, whether fought with swords or words, they are joyous encounters in which love is revealed not only by shared affinity but also by wit, dexterity, and passion.

I feel better for having thought I liked them (I do like them, sometimes!). But I still hope Mark and Elon call off their fight and literally measure each other’s dicks instead. ∎